October- Artist of the Month – Eva Wong Nava

Our October ‘Artist of the Month’ is author Eva Wong Nava.

About Eva Wong Nava.

Eva Wong Nava was born on a tropical island where a merlion protects the inhabitants from marauding pirates. Today, she lives on another island where a pair of dragons protect the City from ill fortune and disaster. Eva writes stories for children that are filled with magic and wonder, as she believes that stories help children navigate their internal worlds and the world outside. Her books have been shortlisted for various awards, and a couple have even won an award or two. When not writing, she can be found at art museums waiting for the next masterpiece to inspire a story. And when not doing that, she goes to schools to talk to students about telling stories through creative writing, and how important it is to read all sorts of books about all sorts of people and all sorts of things.

What a visit from Eva entails

Eva can work with EYFS, KS 1 and 2 for storytelling and activity.

For KS3 and 4, Eva can work with students on creative writing and how to use prompts to write stories.

Her sessions range from 30 mins (younger ones) to 60 mins (older ones).

Before Eva became a children’s book author, she was an English teacher who taught at several inner-city London schools, where many of the students were reluctant readers. She learned that stories engaged students the most as stories made them curious. So, Eva used literature to discuss the bigger questions in life, like what is the purpose of reading, why it is important to represent diverse characters in books, and how literature can help us become more self-aware.

An hour’s session to read and perform Open – A Boy’s Wayang Adventure.

Eva works in an informal and personal style; her sessions are rarely scripted. She lets the students lead and is always happy to answer any questions on the things they are curious about. Eva tends to share personal stories about her writing process and her life. She loves conversations and talking with students and their teachers about writing; she tries to keep her whole presentation fun and interactive. Eva’s sessions always leave space and a lot of time for Q&A

This is what a typical reading session looks like

–Through readings of the book, participants will take a look at how literature can help children understand emotions. They will learn to make connections between their feelings and those of their peers, especially peers with special needs, thus, increasing their own understanding and awareness of personal emotional needs and those of others.

During the session, participants will be sharing and discussing what they understand to be special needs in their families, schools and communities, and why autism is a special need. This is followed by why they think acceptance, tolerance and inclusion are so important in our communities.

As the book interweaves historical elements of the Wayang into the backstory of Open, there will be a short discussion on what the wayang is, how this is related to the history of Singapore (and China) and the importance of preserving our cultural heritage.

Other talks and workshops available.

Sahara Khan uses her special senses to empower her in Sahara’s Special Senses.

Eva can conduct storytelling and creative writing workshops on writing with our senses to your students.

Eva is also available for a reading of her picture book, The Boy Who Talks in Bits and Bobs.

Through music and an activity, your students will be able to empathise with Owen, the boy who talks in bits and bobs.

Creative Writing

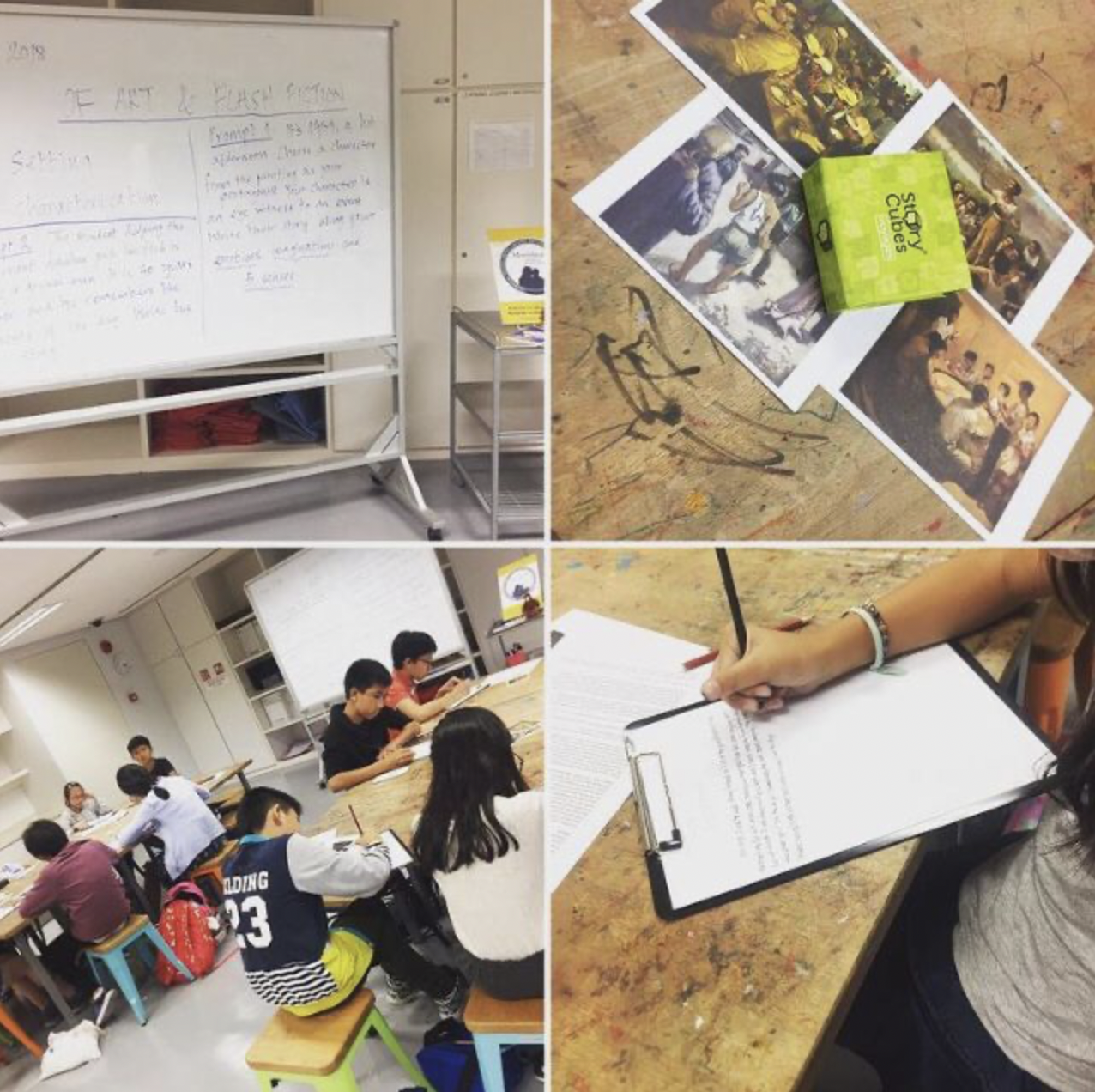

Eva also writes short stories–Flash Fiction–that have been inspired by images. She wants to share how images can become writing prompts and how we can be inspired to write from the images surrounding us.

These courses are typically 60 – 180 minutes long and can be catered to your requirements. The courses can be taught singly or in a set of five. But to maximise on your learning, the latter way is best. This course is good for both children (12+) and adults..

You can read more about Eva and her school visits here

Interview with Eva Wong Nava

What first motivated you to try your hand at creative writing?

Truth be said, I never thought that writing was for me, as the books I used to read as a child were never written by people like me. But, I used to write stories in secret - in my journals or on bits of paper as I’ve always made stories up in my head, and had fun writing them down. One day when I was 12 years old, I submitted a story about a stowaway girl who went on a quest to find her long lost mother and her jade bangle for a contest at my local library. I thought I’d just give it a try. I was surprised when that story won first place, but I thought nothing more of it after, because even then, I didn’t think writing was for me, though I kept on writing secretly. The years passed and I put any chance of a writing career on the back burner to do something else. Soon the children came along and I put aside the writing and read to them instead.

We moved countries twice, and it was only in Singapore, my birth country, that I picked up the pen again. By then I was in my early forties. I was commissioned to write a middle grade book about an autistic boy who found the courage within himself to perform on stage. This rekindled my passion for writing. The book won an award a year later. This somehow reminded me that I can write. And that some people thought it good enough to award me a prize for it, and this gave me the impetus to continue writing. More awards came and this gave me more encouragement. Although I don’t write to win awards, these awards tell me that some people like my stories and want to recommend others to read them. Mostly, I am motivated by young readers and I write for them — children and young adults aged 4 to 18.

When did you know you wanted to be an author as a career?

I’m going to expand on the question and answer it more specifically: when did I know that I wanted to be an author for children, and make this my career?

When my eldest daughter was born, I sought books that would help her understand her identity as a dual-heritage child - Singaporean-Peranakan-Chinese and English. But there were no such books to be found in the UK. So I read the usual books that all British parents would read to their children and I also made sure that I read her stories from other cultures and heritages. To supplement the dearth of stories from East and Southeast Asia (ESEA) in the UK, I made up stories of the Monkey King, the nine-tail fox spirit, and the cowherd and weaver girl, and whispered them in her ear as she was falling asleep, just like what my mother used to do with me, because there was also a dearth of such stories written in English in Singapore. (When I was growing up, all books in English came from either the UK or USA.)

When my second daughter was born eight years later, I repeated what I did with my elder. But this time, the lack of inclusive and diverse books, especially books that lacked ESEA representation, started to bother me. So, I took it upon myself to write down the stories that I used to tell my children. I knew that for my children to read stories that represent half of who they are, I had to write them down and find a way to get them published. I couldn’t give up because their lives and sense of identities and belonging depended on it. And I also wanted to share these stories with other children who come from ESEA backgrounds.

I knew that to get published, I needed an agent. So, I queried agent after agent for some years, and was rejected many times. This was what some agents told me: “I like your stories but I don’t know how to sell them - they’re too niche”, “The market for Asian stories is small”, “I already represent clients with similar stories to yours”.

But I never gave up - I kept on writing stories that centre East and Southeast Asian people, culture and heritage. I kept on submitting them, and finally one day, I found an agent who loved them and was able to sell them. I told my agent that my stories are for everybody because there is a need for more diverse stories. I’m not saying this because I write diverse and inclusive stories that centre my identity and culture as a person belonging to the ESEA diaspora. Diverse stories benefit all children. I know this because as a child I benefitted from reading stories that were set in ancient Greece, boarding schools in England, and in lands that are hot and humid filled with sand dunes and mountains.

How do you research when writing biographies of people?

I go to the National Archives and the British Library for research. At these places, you can find old newspapers and documents that are full of information. These archives have also been digitalised, so for some research, I didn’t have to leave home. There’s, of course, the internet, which is a very helpful resource if you know where to search. Finally, I also read books that have been written about the person I’m writing about.

But first, I have to decide on the person I want to write about. Then I find out as much as I possibly can about that person. After, I let the information percolate in my subconscious until a hook in their lives draws me in. A story hook is something interesting that will keep the reader turning the page because they want to know more. For example in one of my stories about Liu Kang, a Chinese artist who emigrated to Singapore in the 1930s, the hook was how he founded an art movement and style: the Nanyang style. Liu Kang had wanted to go to Tahiti like Gauguin the famous French modern artist, but the Second World War prevented him from going. The hook was in how Liu Kang found his Tahiti in Bali. When I found that hook, the story flowed from there, and writing it down was easier.

Which person would you like to write about in future?

I would like to write about many people as most people tend to have interesting lives. I’m itching to write about the lives of actors Michelle Yeoh and Anna Mae Wong in picture book form. These two female screen artistes showed many people that it is possible to be Asian and be in Hollywood. So far, there are hardly any picture books about their lives. In fact, the UK (in comparison to the USA) is lacking in picture book biographies for young readers, especially of non-European personalities.

Michelle Yeoh is a 21st century Malaysian-Chinese and she won the Oscars for her role in Everything Everywhere All At Once. Although I was born in Singapore, the other half of my family is Malaysian, and I would love to see more Malaysian representation in picture books. Anna Mae Wong was a 20th century Asian-American starlet, who was the first Chinese-American star in Hollywood. A picture book that tells young readers from 6 years old about the life of Anna Mae Wong and how she broke the Hollywood glass ceiling would be a great way to show them that you can be what you want to be, if you set your heart on it. Michelle Yeoh said this when she collected her Oscar trophy, “This is for all the little boys and girls out there that look like me.”

One of your books is about art – is this a subject that interests you outside of work? Are you any good at art yourself?

That’s a great question. I did a Masters in Art History many years after my Bachelors in English Literature. As an art historian, I am interested in how art (and crafts) give us a peek into culture, history, and the artists’ lives. Art is a documentation of the times they were produced. What’s contemporary today becomes modern later on, and then ancient as more time passes.

This picture book - Busy Little Fingers ART — shows children the 10 important art movements in the world. I was very happy to be able to include a contemporary artist - Yayoi Kusama - in the book to make it more inclusive and diverse.

Following from Busy Little Fingers ART is Busy Little Fingers MUSIC (releasing 6, June 2024). This is a picture book on the history of music - it’s cool and funky and a great way for primary school children to learn about the different types of music in the world, starting from Classical music to Folk and Rock & Roll. There is, again, plenty of diversity in this little book.

I love doodling and I do that often. It helps me to relieve stress. I wouldn’t say I’m good at art, but I sketch every now and then for the fun of it. I’m very lucky, though, to be able to work with wonderfully talented artists who bring my words to life with their sketches.

What is your favourite thing about visiting schools?

I love engaging with the students most. It’s the reason why I do author visits.

Young children are great to have conversations with - what they say often generate points for discussion.

For example, I did a workshop with a Year 5 class once, where I talked about World War II through one of my books — Anita Magsaysay-Ho: One of Us. This is a picture book biography (one in a series of four) about the life of Filipino-Canadian artist, Anita Magsaysay-Ho. She survived the Japanese invasion of the Philippines during the Second World War. I chose to read the book to the class because (1) female modern artists were rare in Europe and even rarer in Southeast Asia, and the students learned about modern art from Asia, (2) it gave me the opportunity to introduce a new country that the children in England don’t typically learn about - the Philippines, and (3) the students learned that World War II also happened in Asia, which was very much linked to Europe because of colonisation. All this was because a student asked me where I was from and I said Southeast Asia, which is made up of 11 countries, one of which is the Philippines. With that, I launched into storytelling, reading from the book.

So, with one little book, the Year 5 students at this school learned so many things that day, and they were able to join the dots in their own school curriculum, taking what they have learned or are learning one step further.

What impact do author visits have on schools?

The children benefit the most from author visits in myriad ways. For some younger children, it helps them to see that books are written and illustrated by real people. For older ones, they get to learn something different during the workshops that they will not normally learn about during class time.

You work with a wide range of ages in schools, how do you tailor your visits for such a span?

As a former English teacher, my workshops are planned with scaffolding in mind. I curate my workshops to suit the schools I go to and the age-groups I’m working with. I do this by liaising with the HOD or Teacher-in-charge, asking them what they have in mind for their classes. I send a form ahead of my visit for teachers to fill. This gives me an idea of what to plan for my visit. I don’t want to be teaching the students what they’re already being taught - that’s just plain boring. I want to help students join the dots, but do this by learning something new. During my workshops, I often engage the teachers, and in this way, they also benefit from my visits. As a former teacher myself, I know how important teacher-training is, and I try to incorporate that into my workshops and author visits. I tend to be flexible during my visit, working off-script when necessary, as I believe in giving room to students to express themselves, ask me the burning questions that they want answered, or just tell me what they think of books.

What are your feelings on using fiction to teach young people about serious topics?

I am a fan, of course. Books open windows to different worlds. They are the best resource, in my view, to teach young people about stuff, sometimes even harsh stuff. I don’t believe in molly-coddling children, but I do believe strongly that they need safe spaces to explore their big feelings, and books are a great way and a safe space.

My YA literary historical fiction, which was shortlisted for Best Literary Work for the Singapore Book Awards, tell young adult readers (age 13+) about human trafficking in Southeast Asia during the 20th century. The story helps young adult readers to join the dots about the reality of human trafficking today, in regard to the historical context of indentured servitude. Apart from this, the book is also a lesson on feminism in 20th century Southeast Asia, female agency, and allyship, amongst other themes.

Do you feel everyone has a story within them?

Yes, I do! A child is a natural storyteller. They come home with news about their school day, their school trips or their playdates, and often if you allow them the space, they will embellish their stories with words like “and then this happened”, or “it was so scary when this happened - I had goosebumps”, or “After he said this, I saw how upset she was”.

Do you prefer writing novels or flash fiction, or does it depend on your mood?

I enjoy writing flash fiction as they’re shorter to write. I’m not saying in any way that writing flash fiction is easier than writing the novel. One is a sprint, the other is a marathon, and I was once a sprinter - running the 100 metres.

I’m not much of a marathon runner, I’ll be honest. Whilst I enjoyed writing The House of Little Sisters, my literary YA historical fiction novel, I was constantly out of breath. But having said this, to run in the marathon, one needs training. This is similar to writing the novel, or any other forms of writing, be it long-form or short-form - once you’ve written one novel and learned the ropes, the second novel will be easier. I am working on my next novel. It’s in the planning stage, but with more training, I know I’ll be more fit to write that book.

What tip would you give to inspire reluctant readers to pick up a book or a pen?

Read picture books - you’re never too old to read books with pictures. There are all sorts of picture books - graphic novels, manga, comics, and even illustrated books without pictures. The pictures in picture books tell stories of their own. A picture book is so called because the words and pictures work together - they inter-animate each other - to tell the story. Ask your child who is reluctant to read to look at the pictures and see if they can predict the story without reading the words. A child, who is just beginning to read, one who does not read well yet, is very good at telling their own stories by looking at the pictures.

Remember that stories aren’t only told through words - they can be told through pictures too. So get them to draw their stories instead.

You have worked as a sensitivity reader and champion diversity in children’s books. Why are these so important and what impact can they have when books offer representation of all sections in society?

This is a complicated question to answer, and I will try to be as succinct as possible. In the past, books that had Chinese characters in them were often very denigrating of Chinese people. Take the story of Dr Fu Manchu, written by Sax Rohmer, the first of which were published in the mid-1900s. Dr Fu Manchu was a Chinese master criminal, who was evil and had to be destroyed. The Fu Manchu series was published during a time of the Yellow Peril in the UK, when the fear of East Asians, particularly the Chinese, was at its height. In my search for stories of China written in English, I came across Peter Parley's Tales About China and the Chinese (Simpkin, Marshall and Co, 1843). Parley was the pseudonym for American writer, Samuel Griswold Goodrich, who had, as far as I know, never been to China. This book about China and the Chinese was an exotic rendition of the country at best and a denigrating (textual and pictorial) depiction of its people, at worst. This book just did not sit right with me. Some years later, I picked up David Walliams’ The World’s Worst Children, and read the story about a boy with the surname Wong who could do no wrong (published in 2016), I decided that I had to do something about it. This was also around the time (2015/2016) that I was following what We Need Diverse Books, an organisation that champions diverse book in the USA was doing around issues of misrepresentation. I started to read about what sensitivity reading entailed and decided that this was a way I could help publishers make better books for children.

I am in no way saying that all ESEA characters have to be good. But must they all be evil criminals, nerds with a penchant for maths, or a vamp out to lure innocent men? Diverse characters can be evil, but if your book has only one person of colour in it, then it would behoove the writer to take care about how this ONE diverse character is represented. We are all complex and nuanced characters in real life. Therefore, in portraying people-of-colour, authors who are not people of colour must be mindful of stereotypes, their own personal biases and prejudices. I have done sensitivity reads where authors who are mindful of diversity are eager to throw in a Chinese or British Chinese character or two without taking care to know enough about the culture or the people they’re writing about.

Similarly in the portrayal of disability, often by able-bodied writers, there is a tendency to associate disability with either evil or ugliness.

Sensitivity readers read for many topics and they help make publishers be accountable for the books they produce - after all books are portals to other worlds. Sensitivity reading is important work, but it is often an under-appreciated, underpaid, and emotionally taxing job. I don’t do it for fun, I do it with a mind to help publishing improve and grow. It is important for children to read diverse books with rounded and authentic characters, not ones that are stereotyped and flat. The way all children perceive the world depends on how diverse characters are portrayed in books. It is good to know that sensitivity readers are there to make suggestions not dictate, and these suggestions can either be accepted or rejected by the author. Lastly, the sensitivity reader does not get to read the final version of the manuscript, so they won’t know how their suggestions have been used, unless they read the book when it’s published.

Who comes to you for such work?

My clients are typically editors in trade publishing, who are working on their client’s book that has at least one ESEA character in it, or they are writing about an ESEA culture (usually, Singaporean or Malaysian, or the diaspora culture in Britain) and need my help to make it better. These editors are usually not familiar with the culture and people. I also read for Special Education Needs, like autism and ADHD (due to many of years of reading up on these two neuro-diversities as a teacher and mother). So far, I’ve worked with several trade publishers in the UK and US. I have also worked with book packagers.

I also have clients who are authors themselves who reach out to me seeking help in polishing their manuscripts for submission. Some have been advised by, either, their agent or editor/s to reach out to me.

I also do sensitivity reading for illustrations that represent ESEA people and stories.

Do you feel reading can improve people’s empathy by exposing them to different realities and character’s emotions?

Reading is an immersive activity. When we read, we are immersed in that story world - it is only natural to be. That’s the power of stories. When we are moved by the story, we naturally develop a connection with the characters, and for younger children it is typically with the main character. Reading helps young people understand POV, or points of view. They understand the story world through the characters’ POV, and a magical thing happens, where they then connect what they’re reading about with the world they are living in. Hence, writing relatable characters is important. And these characters can be from any part of the world, belong to a different culture to the reader’s, but as long as they are real and authentic to the reader, they will empathise with these characters.

Which book or author has made a lasting impression on you?

Charmed Life by Diana Wynne Jones. I read this as a child and was so charmed by it, I never forgot the book. And I will add another - The Cats We Meet Along The Way by Nadia Mihail. The latter is the most refreshing diverse YA novel I’ve read this year (2023).

Which fictional world do you wish you could visit?

One filled with magic, wonder and heraldic beasts.

What are you working on the moment?

I am editing my next book - East Asian Folktales, Myths & Legends - which will be releasing on 14, March 2024.

Tell us your favourite fact about Chinese New Year.

I love the food most, I’ll admit. My favourite food is the pineapple tart - bite-sized tarts that you can pop into your mouth whole, made with pineapple jam and baked to perfection, that melts in your mouth. You can find these only in Singapore and Malaysia, as they’re traditional tarts made by the Chinese-Peranakans (aka the Straits Chinese), many of whom have been living in Southeast Asia since the 17th century.

Quick Fire

Starter or dessert?

Dessert first and Starter after!

A quiet night in or dancing?

Quiet night in bed with a book

Would you rather be able to control the weather or talk to animals?

Talk to animals - that would be magical.

What is scarier: a three headed monster that only comes up to your knees, or a hamster the size of an elephant.

Oh hahahah - I love elephants. So I’ll go for the knee-high three-headed monster.

Would you rather have a trip to space or the deep ocean?

Deep Ocean - I would rather float with the fish.

If you were Prime Minister for the day, what law would you introduce?

The Reading For Pleasure Law which decrees that every child in the Kingdom be sprinkled with magic dust at birth that makes them natural-born readers, and to find joy in books.

Arrange for Eva Wong Nava to visit your school

To make an enquiry about Eva Wong Nava, or any of the other authors, poets & illustrators listed on this website, please contact us as follows

UK visits

Email: UKbookings@caboodlebooks.co.uk

Or contact Head of UK Visits, Yvonne - 01535 279850

Overseas Visits

Email:Overseasvisits@caboodlebooks.co.uk

Or contact Overseas Manager, Robin - +44(0) 1535 279853